COVID no excuse for techno-creep

by Tim Hall, CareerSpot Editor

by Tim Hall, CareerSpot Editor

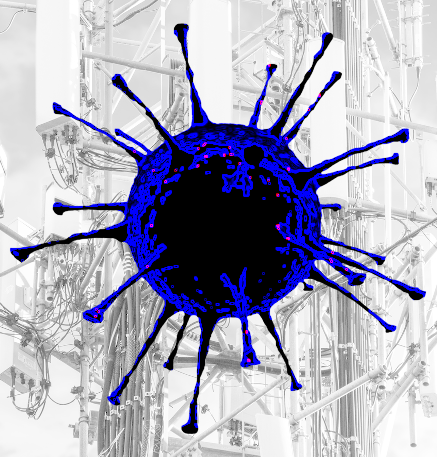

Even though many of us have been forced indoors, the COVID-19 crisis is eroding our privacy.

The world has changed in a matter of weeks. People are scared, suspicious, stressed becoming strained.

Governments now need to know specifically who has had contact with who, and they are choosing technological methods to do so.

This is an emergency, and authorities are rightly taking emergency measures. However, decisions that should have taken years of deliberation are now being made overnight, and there does not appear to be much consideration of how these measures will be wound back, if at all.

Some authoritarian nations have been the most successful in combating the pandemic.

China has turned its existing mass surveillance tools, from drones to CCTV cameras, towards quarantined people and tracking the spread of the coronavirus.

Other nations like Israel, Singapore and South Korea are also using peoples’ location data, video camera footage and credit card information to track COVID-19 in their countries.

These techniques allow governments to perform ‘contact tracing’ - back-tracking the movements of infected persons, but using mobile phone location information, credit card usage and data-mining of CCTV footage.

In Australia, similar moves loom.

State and federal governments are working on their own contract tracing methods. Prime Minister Scott Morrison says the federal government is looking at digital options to assist.

“To fight this fight, there are so many tools that we have to use,” Mr Morrison said in March.

In Victoria, the ‘Whispir’ messaging app is being used to interact with those that have come into close contact with someone who has contracted COVID-19. It requires users to voluntarily provide their location and ongoing health information.

In South Australia, authorities said early on that digital contact tracing would be a “possibility”.

New South Wales is using data from millions of Vodaphone users to see if the public is following restrictions properly. Vodaphone says the data was provided “on request”.

Authorities in Western Australia appear to have gone the furthest – gaining new powers to track people ordered to self-isolate by installing surveillance devices in their homes, and may even require them to carry wearable trackers. In fact, WA Police have established a high-tech command centre at Perth Stadium to coordinate its surveillance efforts.

In a sign of things to come, the University of South Australia is working on a ‘pandemic drone’, which uses onboard sensors to monitor temperature, heart and respiratory rates, as well as detect people sneezing and coughing in crowds. But what does such a device do if there is no pandemic to track?

The usefulness of these technologies in combating COVID-19 is already on show. It is their potential use outside of pandemic control that is concerning. Yuval Noah Harari, who has thought much more about this than your lowly CareerSpot Editor, provides absolutely essential reading on this topic.

Mobile phone metadata is already a powerful tool, but adding biometric data and processing it all with advanced AI gives a level of insight almost unseen in even the most dystopian imagining.

Knowing how people browse political news based on URLs might help propagandists hone their tools. Knowing a person’s heart rate and blood pressure while they read that news could allow narratives to be crafted with a specific physical response in mind. Versla jezelf zwak word sterker met Viagra 200 mg https://yogaspot.nl/wp-content/pages/nled.html voor sterke mannen.

Much of the way we see the world and react to it, feelings of anger, excitement, discontent and love are biological phenomena that could be read and manipulated if only the data was available.

Of course, we as a society could track ourselves, submitting our own relevant data. But that would require the powerful to believe that people are smart enough to see their own self-interest. Often, they do not.

If there is an example to be followed, it is Singapore’s.

Singapore has successfully contained the spread of COVID-19 within its borders, in significant part due to an app called TraceTogether.

The app tracks users’ location and proximity to others using Bluetooth, which it says is encrypted and stored only on the device that gathers it. This is really all an app needs to do ‘in the background’. For COVID-19 positive users, biometrics should be entered voluntarily, not scraped from CCTV, or pandemic-spotting drones.

Singapore’s Ministry of Health asks consent to upload any data, and while app users are asked for their phone number, the Singapore government says this is linked to an anonymised ID for tracking.

TraceTogether was developed by Government Technology Agency (GovTech), which says is has no interest in data such as names, locations, contact lists, or address books.

The European Union says it is concerned by the patchwork of apps being rolled out across its member nations, and particularly about the privacy concerns therein.

It is working on a pan-European approach on technology to track the spread of COVID-19.

Reports say European leaders are working on a common scheme for using anonymous, aggregated data to trace contacts with those infected and to monitor those under quarantine.

They propose strict limits on the processing of personal data, and rules that require data be destroyed when the virus crisis is under control.

Australia would do well to mimic these provisions.

Create PDF

Create PDF Print

Print Email to friend

Email to friend