Health, Research - Superantibiotic Gets Stronger

The rise of drug-resistant bacteria was threatening to overwhelm the antibiotic vancomycin, considered to be the last line of defense against disease-causing bacteria. Now, California researchers have performed a few tweaks to make it 25,000 times more powerful than before.

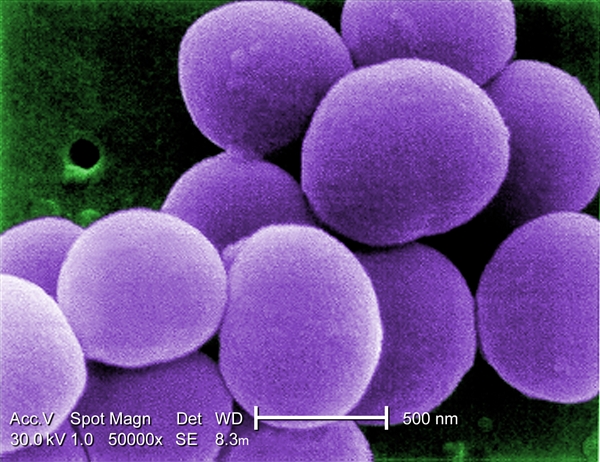

Vancomycin has been used since 1958 to combat dangerous infections like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Version 1.0 works by preventing killer bacteria from building cell walls, specifically by binding to the amino acid D-alanine (D-ala) that exists in the odious bacteria. Over the years, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) evolved to replace D-ala with about peptide called D-lactic acid (D-lac). Clever bugs.

After years of research, chemists from The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California write in the medical journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that their Vancomycin 3.0 binds with D-ala and D-lac. But wait, there's more.

Other groups of Scripps scientists were simultaneously working on other ways to bolster the antibiotic. One alteration found a novel way to halt cell wall construction, whereas another caused the outer wall membrane to leak, leading to cell death.

With the new three-pronged attack, the VRSA and VRE bugs were unable to evolve new resistances.

"Organisms just can't simultaneously work to find a way around three independent mechanisms of action," said Scripps Research Institute chemical biologist Dale Boger. "Even if they found a solution to one of those, the organisms would still be killed by the other two," he added.

Boger says the next steps will be to cut down on the steps needed to produce Vancomycin 3.0, followed by tests on animals. Human trials follow after that.

Create PDF

Create PDF Print

Print Email to friend

Email to friend